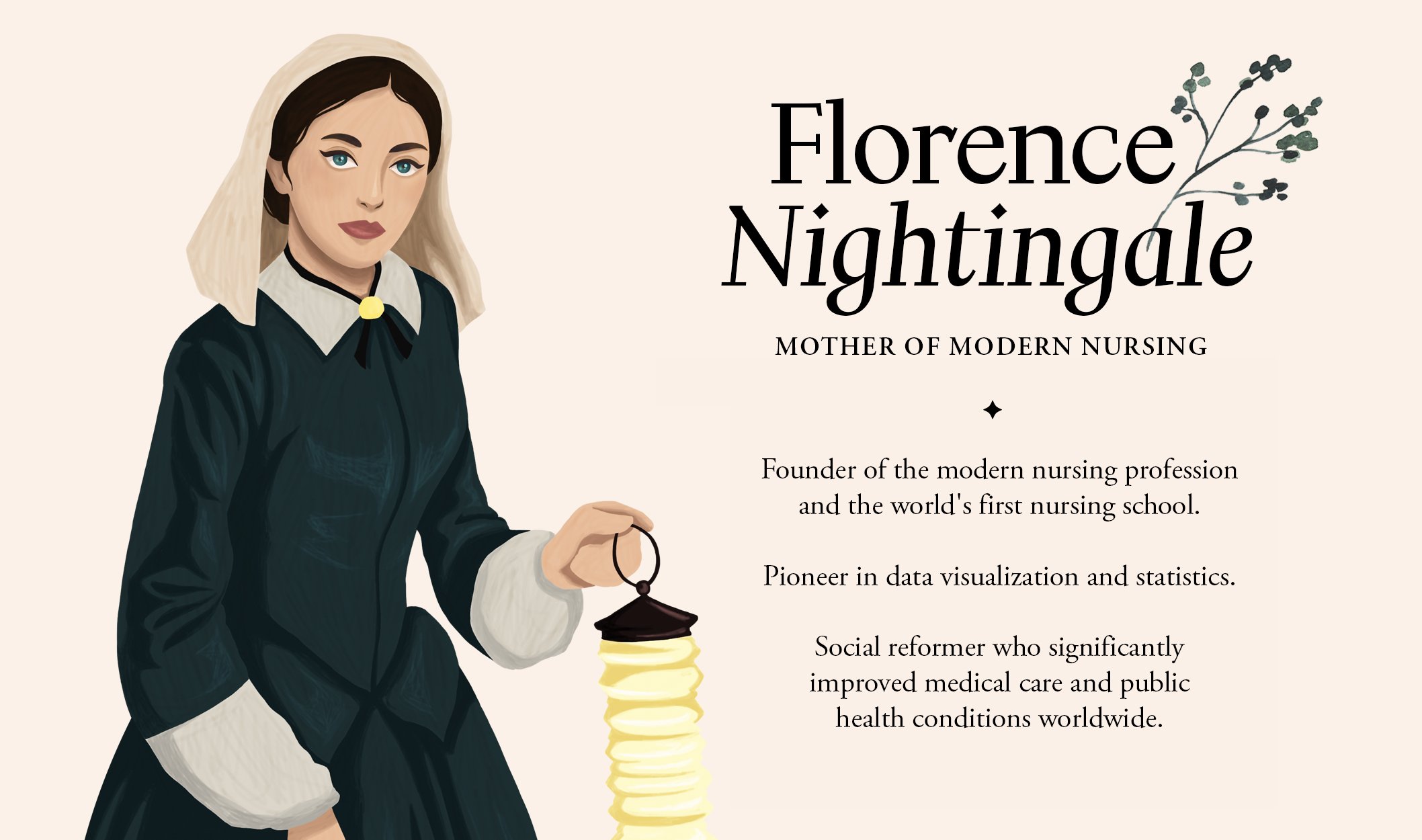

Florence Nightingale (1820 –1910) was an English social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. She rose to prominence while working as a manager and trainer of nurses during the Crimean War, in which she organized care for wounded soldiers in the Ottoman Empire. She elevated nursing to a respectable profession, and became an icon of Victorian culture. She was known as 'The Lady with the Lamp', because she made rounds in the military hospital at night, to care for wounded soldiers.

Florence Nightingale's work played an instrumental role in professionalizing nursing roles for women. In 1860, she established the first secular nursing school in the world. In recognition of her pioneering work in nursing, the Nightingale Pledge taken by new nurses, and the Florence Nightingale Medal, the highest international distinction a nurse can achieve, were named in her honor.

*

Her social reforms included improving healthcare for all sections of British society, advocating better hunger relief in India, helping to abolish prostitution laws that were harsh for women, and expanding women's participation in the workforce.

Florence was an exceptional and multitalented writer. Many of her published works aimed to spread medical knowledge. She wrote some of her texts in simple English, so that those with poor literary skills could understand them. She was also a pioneer in data visualization with the use of infographics and effective presentations of statistical data. Many of her writings, including her extensive work on religion and mysticism, were published posthumously.

*

*

Florence grew up in a wealthy family, from whom she inherited a liberal-humanitarian worldview. Her grandfather was an abolitionist, and her father educated her extensively, having advanced ideas about women's education compared to the social restraints on women in Victorian England.In those days, women from Florence's class did not attend university or pursue a career, their purpose in life was to marry and have children. Florence's father believed women should be educated, and he personally taught her Italian, Latin, Greek, philosophy, history, writing and mathematics. From an early age, Florence displayed an extraordinary ability for collecting and analyzing data, which she would greatly use later in life.

Florence worked hard to educate herself in the art and science of nursing, in the face of opposition from her family and the restrictive social code for affluent young English women. She rejected the expected role for a woman to become a wife and mother, convinced it would interfere with her ability to follow her calling to nursing.

*

In Rome in 1847, she met Sidney Herbert, a politician who would become Secretary of War during the Crimean War, and would be instrumental in facilitating Nightingale's nursing work in Crimea.

In Egypt, while visiting the temples of Abu Simbel and Thebes, she experienced several mystical experiences that prompted a strong desire to devote her life to the service of others. In 1850, she went to Germany and received four months of medical training in a medical institute, which formed the basis for her later care. She later became superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in London.

*

Florence Nightingale's most famous contribution came during the Crimean War, which became her central focus when reports got back to Britain about the horrific conditions of the wounded at the military hospital at Scutari (modern-day Üsküdar in Istanbul). Britain and France entered the war against Russia, in alliance with the Ottoman Empire. In October 1854, Florence and a staff of 38 women volunteer nurses and 15 Catholic nuns were sent (under the authorization of Sidney Herbert) to the Ottoman Empire.

When Florence and her team arrived, they found that poor care for wounded soldiers was being delivered by overworked medical staff. Medicines were in short supply, hygiene was being neglected, and mass infections were common, many of them fatal. There was no equipment to process food for the patients.

*

Florence sent a plea to The Times for a government solution to the poor condition of the facilities, and the British Government commissioned the design of a prefabricated hospital that could be built in England and shipped there. The result was a facility with a death rate less than one tenth of that of the previous hospital.

Florence's efforts reduced the death rate from 42% to 2%, either by making improvements in hygiene herself (for example, implementing hand-washing and other hygiene practices for her staff), or by calling for the Sanitary Commission. However, she never claimed credit for helping to reduce the death rate.

*

Florence believed that most of the soldiers were killed by poor living conditions. Her experience at the military hospital influenced her later career when she advocated sanitary living conditions as of great importance. She turned her attention to the sanitary design of hospitals and the introduction of sanitation in working-class homes. Nightingale’s approach to health care was systemic and holistic. She consistently stressed health promotion and disease prevention.

During the Crimean War, Nightingale gained the nickname ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ from a phrase in a report in The Times:

*

*

The phrase was further popularized by the 1857 poem ‘Santa Filomena’ by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's:

Lo! in that house of misery

A lady with a lamp I see

Pass through the glimmering gloom,

And flit from room to room.

*

Florence Nightingale:

Changing the Field of Nursing

Film by The HISTORY Channel (A+E Networks)

*

*

To recognize Florence for her work in the war, the Nightingale Fund was established for the training of nurses, which received an outpouring of generous donations. As a result, Florence was able to set up the Nightingale Training School at St Thomas' Hospital in 1860, later called the Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery, part of King's College London.

Nightingale wrote Notes on Nursing (1859). The book not only served as the foundation of the curriculum at the Nightingale School and other nursing schools, but also as a classic introduction to nursing for the general public. It was the first of its kind ever to be written, and legitimized nursing as a respectable profession, in a time when nurses were still seen as ignorant and uneducated. Florence spent the rest of her life promoting and organizing the nursing profession. One of Florence's major achievements was the introduction of trained nurses into the workhouse system in Britain since the 1860s.

*

Florence's work served as an inspiration for nurses in the American Civil War. The Union government approached her for advice in organizing field medicine. In the 1870s, Nightingale mentored Linda Richards, America's first trained nurse, and enabled her to return to the United States with adequate training and knowledge to establish high-quality nursing schools there. Richards went on to become a nursing pioneer in the US and Japan.

In 1883, Florence became the first recipient of the Royal Red Cross. In 1904, she was appointed a Lady of Grace of the Order of St John. In 1907, she became the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit.

*

NURSING

Nightingale’s lasting contribution has been her role in founding the modern nursing profession. In addition to starting the first official nurses' training program, she set an example of compassion, commitment to patient care and diligent and thoughtful hospital administration.

In 1912, the International Committee of the Red Cross instituted the Florence Nightingale Medal, which is awarded every two years to nurses for outstanding service. It is the highest international distinction a nurse can achieve, awarded for '“exceptional courage and devotion to the wounded, sick or disabled or to civilian victims of a conflict or disaster, or for exemplary services or a creative and pioneering spirit in the areas of public health or nursing education”. Since 1965, International Nurses Day has been celebrated on her birthday (May 12th) each year.

*

Named in her honor, the Nightingale Pledge (created in 1893) is a modified version of the Hippocratic Oath which nurses recite at their pinning ceremony at the end of training. The pledge is a statement of the ethics and principles of the nursing profession.

During the Vietnam War, Florence inspired many US Army nurses, sparking a renewal of interest in her life and work. The Agostino Gemelli Medical School in Rome, one of the most respected medical centers in Italy, honored Florence's contribution to the nursing profession by giving the name ‘Bedside Florence’ to a wireless computer system it developed to assist nursing. In Istanbul, four hospitals are named after Florence. The Florence Nightingale Museum was establish at St Thomas' Hospital in London in 1989, to celebrate her legacy.

*

STATISTICS

With a gift in mathematics, Florence became a pioneer in the visual presentation of information and statistical graphics. She is credited with developing a form of the pie chart now known as the polar area diagram, or occasionally the Nightingale rose diagram. In 1859, Florence was elected the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society. In 1874, she became an honorary member of the American Statistical Association.

*

SANITARY REFORM

The Royal Sanitary Commission of 1868–1869 presented Florence with an opportunity to press for compulsory sanitation in private houses. She lobbied the authorities to strengthen the proposed Public Health Bill to require owners of existing properties to pay for connection to mains drainage. The strengthened legislation was enacted in the Public Health Acts of 1874.

Florence made a comprehensive statistical study of sanitation in Indian rural life and was the leading figure in the introduction of improved medical care and public health service in India.

*

WOMEN’S MOVEMENT

Florence Nightingale became an icon for English feminists of the 1920s and 1930s. While better known for her contributions in the nursing and mathematical fields, Nightingale is also an important figure in the study of English feminism. An essay she wrote called Cassandra, was included in The Cause, a history of the women's movement. Cassandra protests the over-feminization of women into near helplessness, that Florence saw in her mother’s and older sister’s lethargic lifestyle, despite their education. She rejected their life of thoughtless comfort and chose a life of social service instead. Cassandra was considered a major text of English feminism. Florence was initially reluctant to join the Women's Suffrage Society, but through Josephine Butler was convinced that women's enfranchisement is absolutely essential to a nation if moral and social progress is to be made.

Florence Nightingale's image appeared on the reverse of £10 Series D banknotes issued by the Bank of England from 1975 until 1994. Nightingale has appeared on international postage stamps, including the UK, Australia, Belgium, Dominica, Hungary, and Germany.

*

*

Here, you will find simple and gentle practices, prompts and rituals inspired by Florence Nightingale, that will help you connect with her energy and embody her qualities.

*

*

The exercise: Each day of the week, engage in a secret act of virtue or kindness. Do something nice or needed for others, but do so anonymously. These acts can be very simple, like washing someone else’s dishes, picking up trash on the sidewalk, making an anonymous donation, or leaving a small gift on a coworker’s desk.

This practice helps us look at how willing we are to put the effort out to do good things for others if we never earn credit for it. Zen practice emphasizes “going straight on”—leading our lives in a straightforward way based on what we know to be good practice, undaunted by praise or criticism. A monk once asked the Chinese Zen master Hui-hai “What is the gate [meaning both entrance and pillar] of Zen practice?” Hui-hai answered: “Complete giving”.

The Buddha spoke constantly of the value of generosity, saying it is the most effective way to reach enlightenment. He recommended giving simple gifts—water, food, shelter, clothing, transportation, flowers. Even poor people can be generous he said, by giving a crumb of their food to an ant. Each time we give something away, whether it is a material object or our time, we are letting go of a bit of ourselves and practicing the utmost generosity. Generosity is the highest virtue, and anonymous giving is the highest form of generosity.

Practice by Jan Chozen Bays, from Mindfulness on the Go

*

*

THE EXERCISE

Use loving hands and a loving touch, even with inanimate objects. To remind yourself to practice loving touch, you can put something unusual on a finger of your dominant hand. Some possibilities include a different ring, a dot of nail polish on one nail, or a small mark made with a colored pen. Each time you notice the marker, remember to use loving hands, loving touch.

DISCOVERIES

When we do this practice, we soon become aware of when we or others are not using loving hands. We notice how groceries are thrown into the shopping cart, luggage is hurled onto a conveyor belt at the airport, and doors slamming when we rush.

*

As we do this practice, mindfulness of loving touch expands to include awareness not just of how we touch things but awareness also of how we are touched. This includes not just how we are touched by human hands but also how we are touched by our clothing, the wind, the food and drink in our mouth, the floor under our feet, and many other things. We know how to use loving hands and touch. We touch babies, faithful dogs, crying children, and lovers with tenderness and care. Why don’t we use loving touch all the time? This is the essential question of mindfulness. Why can’t I live like this all the time? Once we discover how much richer our life is when we are more present, why do we fall back into our old habits and space out?

DEEPER LESSONS

We are being touched all the time, but we are largely unaware of it. Touch usually enters our awareness only when it is uncomfortable (a rock in my sandal) or associated with intense desire (when she or he kisses me for the first time). When we begin to open our awareness to all the touch sensations, both inside and outside our bodies, we might feel overwhelmed. Ordinarily we are more aware of using loving touch with people than with objects. However, when we are in a hurry or upset with someone, we can forget to treat them with love and care. We rush out of the house without saying good-bye to someone we love, we ignore a coworker’s greeting because of a disagreement the day before. This is how other people become objectified, and how disconnection occurs.

In Japan objects are often personified. Many things are honored and treated with loving care, things we would consider inanimate and therefore not deserving of respect, let alone love. Money is handed to cashiers with two hands, tea whisks are given personal names, broken sewing needles are given a funeral and laid to rest in a soft block of tofu, the honorific “o-” is attached to mundane things such as money (o-kane), water (o-mizu), tea (o-cha), and even chopsticks (o-hashi). This may come from the Shinto tradition of honoring the kami or spirits that reside in waterfalls, large trees, and mountains. If water, wood, and stone are seen as holy, then all things that arise from them are also holy.

Zen Master Maezumi Roshi teaches how to handle all things as if they were alive. He opened envelopes, even junk mail, using a letter opener in order to make a clean cut, and removed the contents with careful attention. He became upset when people used their feet to drag meditation cushions around the floor or banged their plates down on the table. “I can feel it in my body,” he said. While most modern priests use clothes hangers, Zen Master Harada Roshi takes time to fold his monk’s robes each night and to “press” them under his mattress or suitcase. His everyday robe is always crisp. There are robes hundreds of years old in his care. He treats each robe as the robe of the Buddha. Can we imagine the touch-awareness of enlightened beings? How sensitive and how wide might their field of awareness be? Can we treat everyone and everything, even inanimate objects, with such loving care? How might this practice invite us into different states of being and relating?

“When you handle rice, water, or anything else, have the affectionate and caring concern of a parent raising a child.”—Zen Master Dogen

Practice by Jan Chozen Bays, from Mindfulness on the Go

*

*

Tonglen is Tibetan for ‘giving and taking’ (or sending and receiving), and refers to a meditation practice found in Tibetan Buddhism. Tonglen is also known as exchanging self with other. Below is a simple exercise for practicing Tonglen Compassion Meditation—consciously breathing in the suffering of others, and breathing out relief for that suffering.

1. Find a comfortable position and begin to follow your breath and quiet the mind. After a few minutes or once you are relaxed, you can bring to mind a friend or loved one whom you know is experiencing emotional discomfort or suffering. Imagine that he or she is standing in front of you, and visualize their suffering as a dark, heavy cloud surrounding him or her.

*

2. Move your awareness to your heart area and breathe in deeply, imagining yourself inhaling those dark, heavy, uncomfortable, cloudy feelings, directly into your heart. As you breathe out from the heart area, imagine that your heart is a source of bright, warm, compassionate light, and you are breathing that light into the person who is suffering. Imagine that the dark feelings are disappearing without a trace into the light of your heart; the dark clouds transforming into a bright, warm light at the center of your heart, alleviating his or her suffering.

3. Next, try extending your compassion out to a stranger that may be experiencing dark, heavy feelings at this moment. As you did for your loved one, imagine inhaling these cloudy, dark feelings away from those people into your own heart. As the dark feelings settle into your heart, imagine that they are disappearing without a trace into the light of your compassionate heart. You can imagine this person or people being enveloped by the calm and comforting light that you are breathing out from your heart.

4. Continue the above process of sending and receiving, but this time extend your compassion out to someone you find difficult to associate with. Tonglen can extend infinitely, and the more you practice, the more your compassion will expand naturally. You might be surprised to find that you are more tolerant and able to be there for people even in situations where it used to seem impossible.

Tonglen on the spot

Tonglen can also be practiced informally and on the spot as one bears witness to suffering in everyday life. At any point during the day when you experience personal suffering or observe someone else who is suffering or struggling, you can do Tonglen for one to three breaths.

For example, if you see a mother struggling with an unruly child, you might wish to breathe in the stress and anxiety of the mother and breathe out a sense of calm and ease. You could also practice Tonglen for the child in this situation, breathing in the child’s discomfort and breathing out love and relief. If you see two people yelling at each other, you can breathe in the argument and breathe out understanding. Likewise, you can practice Tonglen for yourself if someone has upset you or something bad has happened.

This can be practiced as quickly as one cycle of breath or you could do it for longer. There’s no need to completely stop whatever you’re doing, just simply put enough energy into staying present with the suffering, without over analyzing or judging it.

Practicing Tonglen on the spot even just three times a day builds the compassion “muscle” in a truly transformative way.

Source: Positive Psychology

*

Learn more about Florence Nightingale, her legacy, and her thoughts on social issues, philosophy, politics, gender, religion and mysticism.

-

✎ Book

‘Cassandra: Florence Nightingale's Angry Outcry Against the Forced Idleness of Victorian Women’

by Florence Nightingale -

✎ Book

‘Notes on Nursing’

by Florence Nightingale -

✎ Book

‘Florence Nightingale’

by Mark Bostridge -

✎ Book

‘Suggestions for Thought’

by Florence Nightingale -

✎ Book

‘Florence Nightingale on Society and Politics, Philosophy, Science, Education and Literature’ by Lynn McDonald (ed.)

-

✎ Book

‘A Brief History of Florence Nightingale: and Her Real Legacy, a Revolution in Public Health’

by Hugh Small -

✎ Book

‘Florence Nightingale to her Nurses’

by Florence Nightingale -

✷ Illustrated book

‘Florence Nightingale’

by Demi -

✎ Book

‘Florence Nightingale on Mysticism and Eastern Religions’

by Gérard Vallée (ed.) -

✎ Book

‘Florence Nightingale, Nursing, and Health Care Today’

by Lynn McDonald (ed.) -

★ Film

‘The Lady With A Lamp’

by Herbert Wilcox -

★ Film

‘Florence Nightingale’

by BBC One -

✤ Article

‘Florence Nightingale, Data Journalist: Information has always been beautiful’

by Simon Roger -

✤ Article

‘How Florence Nightingale Paved the Way for the Heroic Work of Nurses Today’

by Suyin Haynes -

✎ Book

‘Florence Nightingale: Mystic, Visionary, Healer’

by Barbara Montgomery Dossey

Sources:

Medical women and Victorian fiction, by Kristine Swenson

Florence Nightingale: the Lady with the Lamp, by Mark Bostridge

Shining a light on ‘The Lady with the Lamp’, by Amanda Kendal

Nightingale in Scutari: Her Legacy Reexamined, by Christopher J. Gill & Gillian C. Gill

Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 supplement

Nightingale, Florence by Stephen Paget

Image Credits:

Florence Nightingale, an angel of mercy. c. 1855, by Tomkins after Butterworth • Florence Nightingale, Photograph by Henry Hering • Florence Nightingale, by Anne E. Keeling • Florence Nightingale by Augustus Egg • Florence Nightingale by Kilburn • Nightingale receiving the Wounded at Scutari by Jerry Barrett • Florence Nightingale by Henrietta Rae • Florence Nightingale by Goodman • Florence nightingale at St Thomas • Florence Nightingale by Charles Staal • 'Diagram of the causes of mortality in the army in the East' by Florence Nightingale • Florence Nightingale stained glass window at St Peters square, Russ Hamer • Nightingale, The Illustrated London News • 'One of the wards in the hospital at Scutari', by William Simpson • Florence Nightingale at Embley Park in 1858, Photography by William Slater • Florence Nightingale. Photograph after a painting by Herbert